Dr. Paul Connett recommends 10 Key Papers that Challenge Pro-Fluoridation Assertions

INTRODUCTION

Promoters of fluoridation, including public health officials and professional bodies, assert that “Water fluoridation is effective, fluoridation is cost effective, and fluoridation is safe.”

These claims have been repeated so long and so often that, for many, they carry the weight of truth.

As we are becoming increasingly aware, the science to support those assertions does not exist. Nevertheless, the standard assertions have become deeply entrenched articles of faith.

THESE 10 KEY PAPERS CHALLENGE THE 3 MAIN PROFLUORIDATION ASSERTIONS

NOTE: For complete citations, with links and other access to the papers, see SOURCES below.

ON EFFICACY:

1. Brunelle and Carlos (1990). Recent Trends in Dental Caries in U.S. Children and the Effect of Water Fluoridation.

2. Featherstone (2000). The Science and Practice of Caries Prevention.

3. Warren, Levy, et al. (2009). Considerations on optimal fluoride intake using dental fluorosis and dental caries outcomes–a longitudinal study.

ON SAFETY:

4. National Resource Council of the National Academies (NRC 2006). Fluoride in Drinking Water: A Scientific Review of EPA’s Standards.

5. Luke (2001). Fluoride deposition in the aged human pineal gland.

[Also recommended: Luke’s PhD thesis, Effect of Fluoride on the physiology of the Pineal Gland.]

6. Xiang, et al. (2003a). Effect of fluoride in drinking water on children’s intelligence.

Xiang Q, et al. (2003b). Blood lead of children in Wamiao-Xinhuai intelligence study [letter].

7. Choi, Grandjean, et al. (2012). Developmental Fluoride Neurotoxicity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis.

8. Choi, Grandjean, et al. (2015). Association of lifetime exposure to fluoride and cognitive functions in Chinese children: A pilot study.

9. Bassin, et al. (2006). Age-specific fluoride exposure in drinking water and osteosarcoma (United States).

ON COST EFFECTIVENESS:

10. Ko and Thiessen (2014). A critique of recent economic evaluations of community water fluoridation.

NOTE: For complete citations, with links and other access to the papers, see SOURCES below.

WATER FLUORIDATION IS NOT EFFECTIVE IN REDUCING TOOTH DECAY

In spite of strong evidence to the contrary, fluoridation advocates assert that the decline in tooth decay is the result of the increasing numbers of US communities embracing water fluoridation since 1945, today over 60% of the US population.

However, correlation does not prove causation.

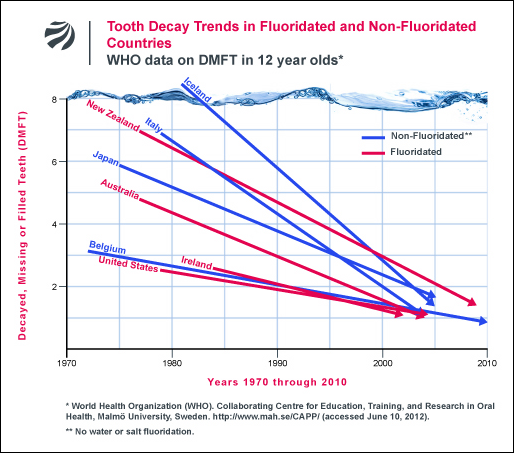

World Health Organization statistics show unfluoridated countries experienced the same steep decline in tooth decay as in the US, during the same period (see fig. 1 below). Fluoride’s mechanism of action in inhibiting tooth decay is topical, not systemic. Water fluoridation is given credit for benefits from the widespread use of fluoridated toothpastes since the 1950s.

Fluoridation’s alleged benefits are challenged by Kentucky, for example, where fluoridated water available to 90% of the population in a state that is number one in toothlessness, and experiences dramatically higher rates of Baby Bottle Tooth Decay (BBTD) than the epidemic rates of BBTD curently experienced in the rest of the US.

KEY PAPERS 1- 3: Although these three studies, Brunelle and Carlos (1990), Featherstone (2000), Warren, Levy, et al. (2009), were conducted by researchers who officially support the policy of water fluoridation, the data generated by the studies support the conclusion that water fluoridation is ineffective in reducing tooth decay.

PAPER 1: “Recent Trends in Dental Caries in U.S. Children and the Effect of Water Fluoridation,” by Brunelle and Carlos (1990), is the result of a government funded survey organized by the pro-fluoridation National Institute for Dental Research (NIDR). With 39,000 children aged 5-17, in 84 communities, it is the largest survey of dental decay in children ever conducted.

The survey found found an average difference of only 0.6 of one tooth surface between children who had lived all their lives in fluoridated communities as compared to children who had lived all their lives in non-fluoridated communities (see Table 6 in the Brunelle & Carlos report). Unfortunately, the difference in tooth decay is not presented as an absolute value (i.e. 0.6 of one tooth surface), but as a relative percentage difference.

Stating a value as 18% looks more impressive than stating a value as an absolute saving of 0.6 of about 100 tooth surfaces in a child’s mouth (128 tooth surfaces when all teeth have erupted). Nor did the authors address the fact that that an absolute saving of 0.6 of a tooth surface is not statistically significant. Instead the authors chose to pad their data with speculative assertions to the contrary (see the Abstract).

Water fluoridation is one of the Four Pillars of US Public Health Policy, and those who challenge it, even inadvertently, risk their careers.

PAPER 2: “The Science and Practice of Caries Prevention,” by John D. B. Featherstone (2000), reaches conclusions that match those of the CDC (1999) and many other oral health researchers over the previous 20 years, that the predominant mechanism of fluoride’s beneficial action is topical not systemic.

Featherstone states: “Fluoride, the key agent in battling caries, works primarily via topical mechanisms: inhibition of demineralization, enhancement of remineralization, and inhibition of bacterial enzymes…Fluoride in drinking water and in products containing fluoride reduce caries via these topical mechanisms.” In other words, there is no reason to swallow fluoride to protect teeth, therefore, no need to mandate fluoridated water.

PAPER 3: Regarding “Considerations on optimal fluoride intake using dental fluorosis and dental caries outcomes–a longitudinal study,” by John J. Warren, Steven Levy, et al (2009), if Brunelle and Carlos (1990) was the largest US government funded study, this was the most precise.

The study is part of the ongoing “Iowa Fluoride Study,” which has been examining tooth decay in a cohort of children since birth. In Warren, Levy, et al. (2009), tooth decay was examined as a function of daily fluoride ingestion (mg/day), with individual exposure studied, rather than the more common comparison of dental decay rates between communities with different concentrations of fluoride in water. The authors found they could not determine a clear relationship between caries experience and daily dose in mg/day.

The authors conclude: “These findings suggest that achieving a caries-free status may have relatively little to do with fluoride intake, while fluorosis is clearly more dependent on fluoride intake . . . . Given that the present study found considerable overlap among caries/fluorosis groups in terms of mean fluoride intake and extreme variability in individual fluoride intakes for those with no fluorosis or caries history [see Figure 2], firmly recommending an “optimal” fluoride intake is problematic.”

FLUORIDATED WATER IS NOT SAFE TO DRINK

KEY PAPERS 4 – 8: There is no question that ingested and inhaled fluorides damage health, but what about the fluoride in fluoridated water? The 500-page landmark review by the National Research Council (NRC 2006) determined that certain subsets of the US public are exceeding the EPA’s safe reference dose for fluoride, including bottle-fed infants, and those with chronic kidney disease.

PAPER 4: Fluoride in Drinking Water: A Scientific Review of EPA’s Standards, by the National Resource Council of the National Academies (2006), reviewed many health impacts for which there is no adequate margin of safety to protect all individuals drinking fluoridated water. These include lowered thyroid function, accumulation in the pineal gland (see Luke et al. 2001)), bone damage, and lowered IQ (see Xiang et al. 2003a,b).

PAPER 5: “Fluoride deposition in the aged human pineal gland,” by Jennifer Luke (2001), documents lowered thyroid function and fluoride accumulation in the pineal gland resulting from ingestion of fluoridated water.

PAPER 6: “Effect of fluoride in drinking water on children’s intelligence” and “Blood lead of children in Wamiao-Xinhuai intelligence study,” by Xiang Quanyong, et al. (2003a,b), found that some children showed decreased IQ at fluoride concentration levels as low as 1.26 ppm; Xiang was one of 42 studies reporting this effect.

PAPER 7: “Developmental Fluoride Neurotoxicity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis,” by Anna Choi, Philippe Grandjean, et al. (2012). The Harvard team found an average lowering of 7 IQ points in 26 out of 27 studies.

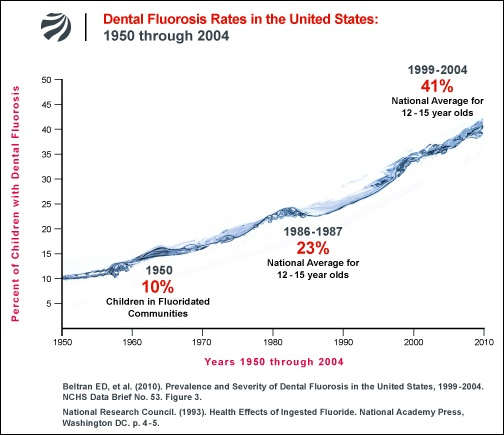

PAPER 8: “Association of lifetime exposure to fluoride and cognitive functions in Chinese children: A pilot study,” by Anna Choi, Philippe Grandjean, et al. (2015), found learning disabilities in children associated even with very mild dental fluorosis, which has relevance for many US children in fluoridated communities (see fig.2 below).

Of the children in this study, Grandjean writes: “Their lifetime exposures to fluoride from drinking water covered the full range allowed in the US. Among the findings, children with fluoride-induced mottling of their teeth – even the mildest forms that appear as whitish specks on the enamel – showed lower performance on some neuropsychological tests. This observation runs contrary to popular wisdom that the enamel effects represent a cosmetic problem only and not a sign of toxicity. Prevention of chemical brain drain should be considered at least as important as protection against caries.”

Dental fluorosis at any level can no longer be considered merely a cosmetic effect.

KEY PAPER 9: Age-specific fluoride exposure in drinking water and osteosarcoma (United States), by Elise Bassin, et al. (2006). Bassin’s disturbing findings indicate that, yearly, some young boys may be losing their lives to osteosarcoma caused by exposure to fluoridated water at 1 ppm, with the greatest risk to boys drinking fluoridated water between the ages of 6 through 8.

This is the only study of osteosarcoma which studied the age at which exposure to fluoride was experienced. The authors write: “We observed that for males diagnosed before the age of 20 years, fluoride level in drinking water during growth was associated with an increased risk of osteosarcoma, demonstrating a peak in the odds ratios from 6 to 8 years of age. All of our models were remarkably robust in showing this effect, which coincides with the mid-childhood growth spurt.” The Bassin osteosarcoma study remains unrefuted.

NOTE: 75% of cases of primary osteosarcoma are found in the age range of 10 to 25 years old and, in that age range, the subjects are almost all male.

WATER FLUORIDATION IS NOT COST EFFECTIVE

How many times have unsuspecting legislators been told that for every $1 spent on water fluoridation $38 is saved? And how many times have those legislators had the time, interest or political will to thoroughly examine that groundless assertion?

It is the responsibility of citizens to inform themselves, then work with their elected officials to strengthen what should be strengthened, and change what should be changed.

KEY PAPER 10: “A critique of recent economic evaluations of community water fluoridation,” by Lee Ko and Kathleen M. Thiessen (2014), examines the real costs of fluoridation in a meticulous analysis of water fluoridation costs that challenges the assertion that water fluoridation is cost effective.

Ko and Thiessen address limitations in the data on which implementation cost analyses are most often based, including referencing the experiences of several utilities directors on real costs. For example, the paper quotes a memo from then Director of the Sacramento Department of Utilities, Marty Hanneman to the City Council (2010):

“The City of Sacramento has been fluoridating its water supplies just over 10 years. Within that time, the actual cost of operating and maintaining the fluoridation systems has proven to be considerably more than the initial estimate…The fluoridation infrastructure at the E.A. Fairbairn Water Treatment Plant is overdue for replacement and will be very expensive to replace…Fluoridating water is a very costly and labor intensive process and requires constant monitoring of fluoride concentrations to ensure proper dosages…The chemical is very corrosive, so all equipment that is used in the fluoridation process has a very short life expectancy and needs to be replaced frequently…but also causes frequent and complex system failures.”

Ko and Thiessen write: “…Recent economic evaluations of CWF contain defective estimations of both costs and benefits. Incorrect handling of dental treatment costs and flawed estimates of effectiveness lead to overestimated benefits. The real-world costs to water treatment plants and communities are not reflected…Minimal correction reduced the savings to $3 per person per year (PPPY) for a best-case scenario, but this savings is eliminated by the estimated cost of treating dental fluorosis.”

Water fluoridation is not effective, not safe, not cost-effective. Note that in the 70 years since water fluoridation was launched, there has never been a Randomized Control Trial (the FDA gold standard to determine a drug’s efficacy) to establish that ingesting fluoride, in fluoridated water or in fluoride supplements, reduces tooth decay.

Future historians may well be astounded that, in the handful of countries that fluoridate, so many public health agencies and respectable professional associations endorsed a practice that had so little scientific evidence supporting it.

SOURCES: Citations with links and other access to the 10 Key Papers

Bassin, Elise et al. 2006. Age-specific fluoride exposure in drinking water and osteosarcoma (United States). Cancer Causes and Control, May;17(4):421-8. A PDF of the paper is available on request.

Brunelle, JA and JP Carlos. 1990. “Recent Trends in Dental Caries in U.S. Children and the Effect of Water Fluoridation.” Presented March 1989, at a Joint IADR/ORCA International Symposium on Fluorides. Published February 1990, Journal of Dental Research, (Special Issue) 69 :723-727.

Cecil, James C. 2004. Kentucky is Number 1 in “Toothlessness.” Kentucky Epidemiologic Notes & Reports V39:4. Cabinet for Health and Family Services, Division of Epidemiology & Health Planning of the Kentucky Department of Public Health. PDF

Choi, Anna, Philippe Grandjean, et al. 2012. Developmental Fluoride Neurotoxicity: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis. Environmental Health Perspectives, 120(10):1362–1368.

Choi, Anna, Philippe Grandjean, et al. 2015. Association of lifetime exposure to fluoride and cognitive functions in Chinese children: A pilot study. Neurotoxicology and Teratology, 47:96–101. A PDF of the report is available on request .

Connett, Michael. 2012. Tooth Decay Trends in Fluoridated vs. Unfluoridated Countries.

Connett, Michael. 2012. Dental Fluorosis in the U.S. 1950-2004.

Connett, Paul. FAN Bulletin (December 22, 2014)

Featherstone, John DB. The Science and Practice of Caries Prevention. JADA 131(7):887-99. (July 2000). PDF.

Ko, Lee (Oakland, CA) and Kathleen M. Thiessen (Oak Ridge Center for Risk Analysis, Oak Ridge, TN). 2014 “Review: A critique of recent economic evaluations of community water fluoridation: A critique of recent economic evaluations of community water fluoridation.” International Journal of Occupational and Environmental Health.

Luke, Jennifer. Fluoride deposition in the aged human pineal gland. 2001. Caries Research Also recommended: Luke, J. 1997. PhD thesis: Effect of Fluoride on the physiology of the Pineal Gland.

National Resource Council of the National Academies (NRC). 2006.

Fluoride in Drinking Water: A Scientific Review of EPA’s Standards.

Warren, John J, Steven M. Levy, DDS, MPH, et al. “Considerations on optimal fluoride intake using dental fluorosis and dental caries outcomes–a longitudinal study.” Journal of Public Health Dentistry, 69(2):111-15.

World Health Organization (WHO) Collaborating Centre for Education, Training and Research on Oral Health, Malmö University. 2012. DMFT (Decayed, Missing & Filled teeth) Status for 12 year olds by Country. Oral Health Database (2012).

World Health Organization (WHO) International water fluoridation and DMFT rates statistics: PDFs are available on request.

Xiang Quanyong, et al. 2003a. Effect of fluoride in drinking water on children’s intelligence. Fluoride 36(2):84-94, and Xiang Quanyong , et al. 2003b. Blood lead of children in Wamiao-Xinhuai intelligence study. Fluoride 36(3):198-199, Letter to the Editor. PDFs of these papers are available on request.